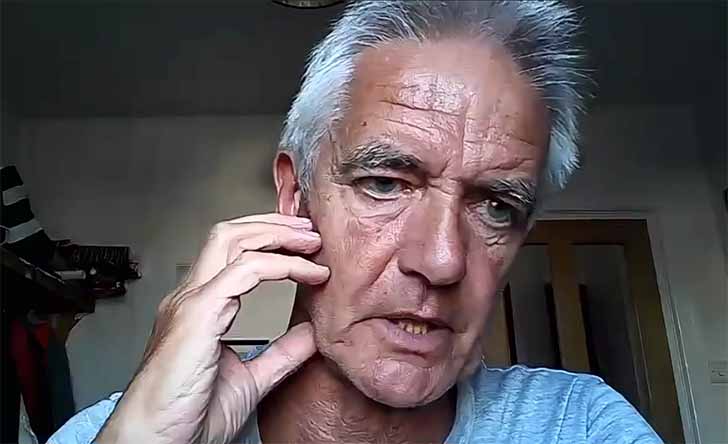

PA’s Alan Jones says:

‘Unions are back in the news, big time’

COULD we be on the tip of a new golden age for industrial correspondents?

Over more than a year of intense, nationwide industrial action, rumour has it that certain media outlets have been scrambling to find reporters with union contacts to cover the storm of labour disputes sensibly. The June/July edition of the NUJ house magazine the Journalist even splashed a feature about the revival of industrial journalism: 'Labour correspondents strike back'.

But if there's a renewed interest in labour coverage, that must have meant it went away at some point. Where did it go? And why?

Alan Jones: "I find it quite staggering that nobody else has anyone reporting on trade unions given the year we've had."

On the very same day that the Journalist's cover story was published, NUJ London Freelance Branch welcomed long-time industrial correspondent with PA, Alan Jones, to chat with members about the historic waning – and possible revival – of accurate reporting of strike action, unions and workers' rights. (The PA is the Press Association, the UK news agency owned mostly by the newspaper publishers.)

"I'm the last national reporter reporting fairly on trade unions!" he joked, darkly. "When I started on this beat, every single paper, radio station and TV station had a labour correspondent, as they were called. We had three. It was the top job everywhere."

Jones harked back to a time when the top news story every day would be about strikes or union conflict with the Labour Party – some things never change – but recounted how this declined as unions became less powerful during the 1980s. He identified the turning point: the mid-1980s miners' strike.

"It was the high benchmark for labour correspondents. But when the miners lost that dispute, there was less interest in trade unions. They had less power. Newspapers started doing away with their labour correspondents. And fast-forward to now... it's basically just me and the Morning Star who go to trade union conferences."

Until very recently, that is. Just a few weeks ago, 21 June marked the first anniversary of the first major rail strike by members of the RMT. Jones described how over the past year he had been writing up to 10 stories a day about new and ongoing industrial disputes, and strike ballots being announced. And this time it's not miners and dockers, but the likes of doctors, nurses, teachers and barristers. Other things have changed too...

"The way the way people on strike have been treated – even nurses – has been appalling; you know, vilified. Mick Lynch, who I speak to a lot, has had people following him, going through his bins, checking his son's Facebook page, and so on. I can tell you all kinds of horrible horror stories."

So what happened between the mid-1980s and now? People did not stop working in industries, after all. Did newspapers find an alternative way of covering labour issues?

"Back in the 1980s," said Jones, "journalists with the title of 'labour correspondent' did it properly. They went to union conferences; they spent all their day talking to trade union leaders; they knew exactly what was happening with the executive. But when that job fell off – which it did, big time – nobody took over.

"Up until this last year, it would be city editors, political reporters and general reporters who were reporting on trade unions. And it was only about strikes: there would be nothing about all the other work that unions do, which I write about. And, obviously, city reporters have a completely different view on a story."

That last point is key to the problem, he said. When he writes about monthly unemployment figures, for example, he naturally gets a quote from the TUC or Unite, or from a campaign group. His city desk colleagues, on the other hand, would not dream of quoting a union leader when covering the same story; they would quote a city analyst instead.

In the same way, a media outlet would probably send its health reporter to cover the junior doctors' strike. "But, you know, health reporters, they'll just look at it from the impact of the effect on cancellations of appointments. Very few reporters now will look at why so many people going on strike; looking at their horrendous pay."

Even political reporters have a completely different way of looking at stories, most of it being biased against trade unions and the Labour Party, according to Jones. "Look at the annihilation of Jeremy Corbyn and the attempt to annihilate Mick Lynch... but they haven't managed that because he's brilliant in the media."

TV reporting is just as slanted: "They'll stand at Waterloo station and say, 'Look, there are no trains running, isn't it appalling?' If it's a health strike, they'll stand inside a hospital and say 'No-one's having an operation today, isn't it appalling?' If it's an education reporter, they'll be in an empty school classroom and say, 'The children aren't in school today because of the strike'. This happens a lot.

"I report on these things as well. I will say why the teachers are on strike, what they've been offered, how much below inflation that is, and how much they've lost in the last year. When Mick Lynch points out that some train drivers haven't had a pay rise in four years, that for me is the story. Not that someone can't get to a bloody Epsom Derby or something on a Saturday."

Are trade unions themselves at fault for this unfair coverage? Do they do enough to get themselves in the news?

"There's no question unions are trying; they're doing a fantastic job," reckoned Jones. "Unions are really switched on to social media, for example. It's just that they are either ignored or whatever they put out is skewed against them.

"Back in the day, unions hardly ever had press officers. It was usually some union official who dealt with the press. Now, every major union has a Campaigns and Communications department, sometimes staffed by ex-journalists. The quality of the stuff they put out is genuinely good."

Local newspapers are particularly difficult to work with, he said. Not only do they not employ anyone to write specifically about industrial relations, many of them do not even have any staff reporters. They may be happy to take agency copy, such as Jones' own stories for the PA, but unions often say they enjoy little success contacting local papers directly. And this is a shame, notes Jones, as nationwide strikes have local interest, affecting every part of the country.

Naturally, Jones said he was appalled at the progress of the government's attempt to introduce spiteful anti-strike legislation, spearheaded by Grant Shapps when he was Transport Secretary and being made to look foolish by Mick Lynch.

"I think if one nurse, teacher or railway worker is sacked, which is possible under this legislation, that is going to be a massive story for me," he said. "But the political reporters will probably say, 'Oh, isn't it good of government to take action to make sure trains turn up on time?' That's the massive difference in the way these things are covered."

When asked whether he thought industrial relations coverage was any better in left-leaning newspapers such as The Guardian and the Daily Mirror, Jones was doubtful. "Neither of those papers have industrial correspondents. The Daily Mirror does not have a single reporter who covers trade unions. Even The Guardian will have their specialist reporters cover these things. I do not know why, even this last year, they haven't appointed someone to cover all the strikes."

Do the strikers themselves have a different profile than they did 30 years ago?

"I would say most of the people who've been on strike in the last year have never been on strike before. So obviously, barristers, junior doctors, teachers, and a lot of civil servants. And that has been one of the big aspects of this last year. I think it has changed a lot of people's views of trade unions.

"I'm not sure it's changed the coverage of them, to be honest. Most of the national papers still attack unions for what they're doing. But I do think it has strengthened the trade union movement, and I think people like Mick Lynch have raised the bar, if you like, in terms of someone who can put forward what unions do."

Amid the questions and answers, LFB member Nick Jones jumped in with his own take on the hailed revival of labour coverage in the media. Nick Jones is the author of The Lost Tribe of Fleet Street, a book recounting the loss of industrial correspondents across all newspapers in the 1990s.

He said he was fascinated by "a sort of new generation of younger reporters coming up through social media, reporting on strikes and homing in on disputes like that one involving Amazon". He also wondered whether newspapers would continue playing an anti-union card when the General Election comes around. "If you think of the women who now lead the biggest unions, I think there is a change. The union movement has sort of raised the bar a bit, and there's a greater public awareness," he observed. "I don't think [the anti-union newspapers] are going to have quite as much ammunition as they had back in the Thatcher era."

Overall, he said, he was encouraged by the signs of revival in the reporting of industrial disputes, especially online.

Alan Jones said he was not so sure: "I still look at national newspapers as the way many people get their news. And it's still so biased. There's no question at the next election, most of the national newspapers will be anti-Labour, which means there'll be anti-union. That's not going to change."

Does broadcast media do a better job in terms of fairness and impartiality?

"When they go and do live interviews, yes," he agreed. "You can't edit an interview if you're doing it live from a picket line, which is why the RMT always tried to do live interviews. For that very reason, Mark Serwotka [General Secretary of the PCSU], when he announced the first big civil service strike, he did it at a press conference that was broadcast live. He did that because he knew that Sky and the others couldn't just doctor what he said.

"But in terms of general coverage… I mean, have you ever watched GB News? Or listened to Times Radio? They're just as bad as the right-wing newspapers. So it really is down to the BBC, as it always is, to try and get a kind of balanced report on what's happening."

To wrap up, what advice would you give to early-career journalists looking to become industrial correspondents?

"Contact every trade union press office and make them send you their press releases. You will get stories that nobody else is writing. Because every day I get 20 to 30 press releases or calls from a trade union communications officer or an official. So if you were just doing that, if you were starting off, there is no question you will get a story.

"Whether you be able to sell that, as a freelance to a national newspaper, is another matter. But you know, there are so many other ways of selling stories now: the importance of social media, the internet, every newspaper has a website… They need stories to fill!

"But that would be my advice: contact the press office of every major trade union, and you will get loads of stories."

![[Freelance]](../gif/fl3H.png)