Interview: Alison Joyce of St Brides, Fleet Street

‘We are here for all journalists’

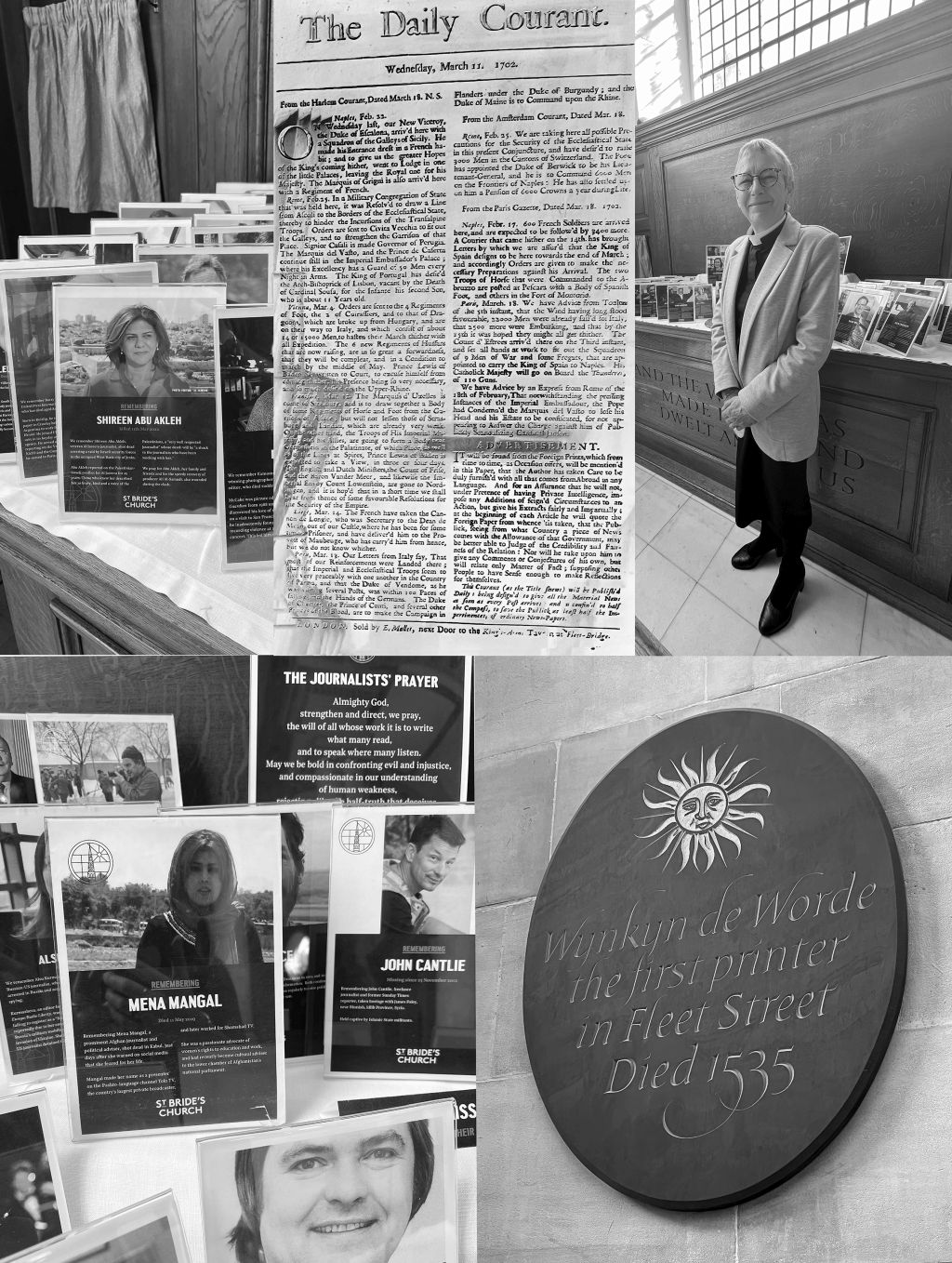

THE FREELANCE interviewed Alison Joyce, the vicar of St Bride’s – the Journalists’ Church on Fleet Street. We talked in front of the journalist’s altar on 7 May, four days before the two-year anniversary of Israeli forces killing Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh on 11 May 2022. Shireen was shot dead by an Israeli soldier while reporting on an Israeli military incursion into Jenin refugee camp. The altar displays photographs of hundreds of deceased and missing journalists.

Left to right, top row: Shireen Abu Akleh remembered on the journalists’ altar; the world’s first newspaper, a plaque of the Daily Courant; Alison Joyce in front of the altar.

Bottom row: A detail of the altar; blue plaque to Wynkyn de Worde

The Freelance: How did the altar come to be?

Alison Joyce: It dates from 1986, when John McCarthy and Terry Anderson were held hostage in Lebanon. We didn’t know what their fate was. All-night vigils took place at St Bride’s. In 1991 John McCarthy came to St Bride’s after his release. He had a special service; he came to give thanks for the spiritual support. In 2021, on the 30th anniversary of John McCarthy’s release, he recorded a radio programme here at the journalists’ altar. It’s lovely we’ve still got that link with him 30 years on; and that was the origin of what we see today. A picture of Terry Anderson, who’s just died, is at the front.

We have eight plaques with the names of all journalists killed in Gaza. There are so many names. But at the back, there’s a little memorial plaque to a journalist who was 23. Most people won’t have heard of her: she was called Rachel Nurse. She died of ovarian cancer, and she was just starting out on a local paper, the South Wales Argus. So, we really are here for all.

And Shireen Abu Akleh is remembered at Saint Bride’s?

Yes, of course we worked with Al Jazeera for her memorial service. Right at the front, you’ll see plaques to those who are in prison, held hostage or missing. We don’t know what has happened to John Cantlie since he was captured in Syria in 2012. We haven’t heard anything since 2020 apart from short videos; but his family know that we do not forget him.

We have Marie Colvin – the famous photo of her wearing her black eye patch that tends to feature in news coverage of her was taken in front of the altar here.

We’re here for all journalists, the world over, for journalists who are freelance, who work on little obscure regional papers, for everyone who works within the industry: photographers, translators. On the wall by the altar there’s a memorial to those who died covering the war in Iraq, which includes journalists from Al Jazeera, Argentine TV, Reuters and the BBC. That monument tells you everything you need to know about the international nature of our ministry. It’s for anyone who works in the industry because very often it’s the support staff who are most vulnerable, particularly when they are translating. The world has changed so much that having “press” on the front of your flak jacket can make you a target rather than give you protection.

What’s unique to your role as vicar of Saint Bride’s, supporting journalists?

It’s unique across the world: it’s the only church with this specialist ministry. It was the Printers’ Church from the year 1500, when printer Wynkyn de Worde inherited William Caxton’s press and took the brilliant economic decision to move the press from Westminster to next door to us in Fleet Street. Because we’re on the road between the City of London and the City of Westminster, you’ve got the clergy, the lawyers: other presses followed. This became the hub of the printing industry. Because this is where the printing was, it is where newspapers originated. The first national daily newspaper, the Daily Courant, was printed in 1702 on Fleet Bridge and was produced by a woman, Elizabeth Mallett. People sometimes forget that a woman produced the first newspaper. We’ve got a facsimile of the first edition on a brass plaque.

When you learn of unethical practice within the press, how do you respond to this as a vicar?

There are some outstanding journalists working for pretty disreputable newspapers, just as there are some pretty disreputable journalists working for outstanding newspapers. So, we do not discriminate in that way. We are here for all, and we minister to all, without distinction.

However, our unique role with the press does mean that we have a voice, and we use that voice as strongly as we possibly can to uphold ethical standards in journalism and our need for journalists. We fight that battle not by turning anyone away, but by doing everything we can. We have an annual lecture here which often touches on those kinds of things. It’s not a one-person battle and I wouldn’t get very far if it was, but we do have a place to wave the flag for quality journalism.

It’s worth remembering that journalism isn’t free because people have got their BBC News app. There’s a generation who’ve grown up assuming news is free: we need to remind people it’s costly, both in financial terms and in human terms.

The saying “if it bleeds it leads” means you’re ministering to people who work in an industry where that is a cliché: what does that mean to you?

I happened to be travelling from Jerusalem to the West Bank on 7 October, so I was caught up in the first few days of that conflict. We had no idea what was going on, what was going to happen; and I was acutely conscious that while the people I was with were desperately trying to get out, the journalists were desperately trying to get in.

That was very sobering and chastening because it’s the first occasion I’ve been in the thick of an unfolding conflict.

I’ve been in earthquake zones, but I’ve never been in that kind of volatile conflict situation, just when it broke out.

I have such tremendous respect for those journalists as a result. I think it brought it home to me in a very acute way that, when a bomb goes off, it really is the journalists who run towards it when everyone else is evacuating.

And I suppose there comes a point where journalists can’t do that anymore?

Absolutely. I think one understands why there’s a disproportionate amount of alcoholism and rates of suicide amongst journalists. It’s quite startling, when you see what they are exposed to during their work, and some of them I don’t know how they survive. I do know of one outstanding journalist who switched from doing defence to something else, who said that she had just seen one too many massacres.

![[Freelance]](../gif/fl3H.png)