Journalists under threat in Latin America

ON SUNDAY 2 November London Freelance Branch held a symposium in partnership with King’s College London’s University College Union branch to mark the annual UNESCO day calling for an end to impunity for crimes against journalists. For an overview of the event see here.

Grace Livingstone holds up the name of a journalist killed in Gaza at the close of the event on 2 November

GRACE Livingstone has reported from Latin America for over 20 years for a wide range of outlets including the BBC, the Guardian and the Observer, and is the author of three books including America's Backyard: a History of US Interventions in Latin America – and is vice chair of London Freelance Branch. She discussed with Ali Rocha, the founder of Brazil Matters, the fight for justice following the murders of journalist Dom Phillips and indigenous rights campaigner Bruno Pereira on assignment in the Brazilian Amazon in June 2022. As Ali pointed out, because Dom was foreign more was done to find his killers while other journalists in the region remain at serious risk from criminal gangs operating in the Amazon.

Grace Livingstone: For any of you who don't know, Dom Phillips was a British journalist, mainly writing for the Guardian, and Bruno Pereira was an expert on indigenous peoples, and they were killed in the Amazon in Brazil in June 2022. Ali, could you explain what happened and why they were targeted?

Ali Rocha: Dom Phillips and I were both members of the association of foreign journalists in São Paulo, and we were interested in the same stories. Most of the correspondents cover the economy and party-political stories. Dom was, like me, more interested in human rights stories and environmental stories. So we used to discuss those sorts of stories and their strange contexts.

I remember vividly the day that we first heard of the disappearances of Dom and Bruno, 5 June 2022. We were immediately very worried because that was the final year of the far-right government of President Bolsonaro, under which all the protections for the environment and indigenous peoples were dismantled in Brazil.

Bolsonaro was outspokenly anti-indigenous, anti-environment and a climate change denier. The violence against environmental defenders and journalists increased extraordinarily during his government.

Bruno was researching a book about environmental problems – he was talking with the people, with indigenous communities, with traditional peoples. He wanted to talk with them to find solutions for climate change.

Journalists have been investigating all sorts of criminal activities in different parts of the Amazon. Dom teamed up with Bruno Pereira, who was an indigenous expert who used to work for the national indigenous agency of Brazil, FUNAI. He used to work mostly with isolated indigenous peoples.

During Bolsonaro's government, Bruno was unable to do this work, so he took leave and went to work with an indigenous organisation in the Javari Valley, which is in Brazil on the border with Peru and Colombia. That is where they were eventually murdered. He was looking at a network involved in poaching and illegal fishing of the Pirarucu, a giant Amazon fish.

Because of this work, Bruno constantly received death threats. He had a target on his back. Dom knew this but at the same time felt safe. because they were working directly with those indigenous peoples, who did their own surveillance of the site, and knew that area like no one else.

The day that Dom and Bruno went missing, they were going to talk to one of the guys who was allegedly involved with one of these criminal organisations. They were supposed to arrive at a certain place at a certain time – and they didn't. Immediately the alarm was sounded – but the government did not [search for them]. The indigenous peoples themselves went searching for them, and my journalist colleagues.

Bolsonaro said at the time that Dom and Bruno “were on an adventure that is not recommended”. The suggestion was that people didn't like Dom, because he asks too many questions and there's lots of people who don't like him, the miners, the loggers, lots of people don't like him... At the same time we had the Ministry of Justice saying that they were sending helicopters out – and the people on the ground, the indigenous people, said that was not true.

Eventually, 10 days later, they found the remains in the Javari Valley. They'd been shot, dismembered and burned.

Grace Livingstone: Can you just tell us a bit about the investigation? Do we know who killed them? Has anyone been prosecuted?

Ali Rocha: Because of the threats that Bruno had received, the indigenous people immediately had suspects, and two men were arrested, then charged with shooting them and trying to dispose of their bodies. Later another man was arrested on suspicion of being the mastermind, one of the leaders of the criminal gang. These three men are currently in prison, but are still not convicted. Justice in Brazil is very slow.

Grace Livingstone: And are other journalists in Brazil covering the environment or indigenous peoples still under threat? Jair Bolsonaro is no longer in power. I think most people know who he is – the Brazilian Trump. He's just recently been convicted for leading a coup, because he wanted to stay in power. There's a new government now – is it better for journalists now? Or are journalists still under threat in areas such as the Amazon?

Ali Rocha: It's much better now. Bolsonaro has three sons who are politicians, and they were all very hostile towards journalists in general. Journalists who didn't support them were being harassed, were being mistreated, were even being attacked by Bolsonaro's supporters. That's no longer happening.

But in the Amazon specifically – it is a very remote area and it's very difficult to access. Some areas are considered lawless. It's impossible to police all the areas deep in the forest. Many areas in the Amazon are only reachable by boat.

In 2024 Scorched lands of journalism in the Amazon, a report by Reporters Without Borders, described the danger of being an environmental journalist in the Amazon. The same year that Dom was killed, another journalist was killed in the north-east of Brazil because he was reporting on another criminal organisation and on criminals who have been arrested, convicted, charged with two homicides. That story wasn't even heard. It didn't really make national news or anything.

The fact that Dom Phillips was a foreign journalist and we've had international repercussions forced the authorities to actually take action.

But it is very, very dangerous for journalists to report in the Amazon because most of the criminal gangs that operate illegal logging, land-grabbing and deforestation are supported by local politicians and by big businesses in the area.

Grace Livingstone: That's very similar to Mexico, where journalists in Mexico City are under threat, but when you go out into the regions, journalists focusing on local authorities, criminal gangs, corruption, municipal authorities... the highest numbers of killings and threats [are] out in the regions, because they have very little protection.

Today, we're talking about impunity for crimes against journalists, and there's a famous case of a journalist in Brazil, Vladimir Herzog, who was murdered during Brazil's dictatorship, which was from 1964 to 1985. Bolsonaro is a defender of that dictatorship. Herzog was tortured and killed, and no-one's ever been prosecuted for that death, have they – can you just say a bit about that?

Ali Rocha: No one has been prosecuted for any crimes that occurred during the dictatorship, because they had an amnesty over the dictatorship. There were several attempts to review this, especially over disappearances.

Vladimir Herzog had worked for the BBC, for the Brazilian service. He was not part of any political organisation. He was just a journalist, and he went voluntarily to the prison [to be questioned, on 24 October 1975]. He was tortured, and it was announced that he was found hanging in a cell the same day: But it was obvious that they had set this up. That was 50 years ago last week.

For many years his family fought for justice. They knew he had not committed suicide. A few years ago, this was recognised: the family finally received a rectified death certificate [recognising that he died] because of the violence from army officials during the dictatorship 50 years ago. [Early this year his widow Clarice was granted a pension.]

I think we can do more. The police were never reformed. The security departments, the institutions in Brazil were never reformed. So, such practices are still widespread in prisons, in police stations; torture is still widespread. We live under democracy, but it's a partial democracy, because it's a democracy that only applies to white people, to people from the middle classes.

The people who live in the favelas have no rights. They constantly suffer violence, all sorts of violence from the police. The state violence in Brazil today is directly connected to the fact that no one was ever punished for the crimes during the dictatorship.

Grace Livingstone: I wanted to talk a little bit about the rest of Latin America. I've mentioned Mexico, where more than 150 journalists have been killed in the last three decades. More than 20 have been disappeared. Amnesty and PEN had a vigil outside the Mexican embassy this week on the Day of the Dead. They were demanding an end to impunity for crimes against journalists.

One of the things that Amnesty is calling for is for the British government to ratify the International Convention on Enforced Disappearances. The British government says, “we've signed other conventions on other crimes” – but enforced disappearances are a specific crime, not the same as murder, because you don't have a body. It's not the same as kidnapping, because you don't know where the person is. It's a particularly horrible crime for the family because they don't know what's happened to their loved ones.

It doesn't just affect journalists in Mexico. Palestinian journalists have been disappeared. In lots of other places in the Middle East, in Colombia... Amnesty's campaign at the moment is to get the British government to ratify that convention.

In Peru, there are these massive “Gen Z” demonstrations. Previous demonstrations managed to get rid of quite a repressive president, and now there's an interim president who's very similar, and 300 journalists in the Peruvian press association have come out and said that they're extremely concerned about the threats against journalists; over the last three years they've massively increased.

You've probably all heard of Javier Milei in Argentina -- the one who holds the chainsaw and is a friend of Elon Musk and Donald Trump. Since he's come to power Reporters Without Borders have said there's been a big increase in threats to journalists coming from the state.

To give one example: Javier Milei himself sent 93 aggressive Twitter posts in the space of 48 hours to one journalist. His allies were sending threats. The journalist, Julia Mengolini, subsequently faced sexual threats, and death threats, because of the rhetoric of Milei and his allies.

Milei said in May “we do not hate journalists enough.” He's called them “politicians”, “prostitutes”, “hitmen with press cards”. This has led to physical attacks on journalists and Milei has launched a sort of legal warfare against journalists, with defamation suits. One journalist, for example, has tapes of Milei's sister talking about an alleged bribery case, and he's got an injunction against the journalist.

It's a really dangerous situation for journalists in Argentina. Similarly, in El Salvador, you probably know that President Nayib Bukele is another Trump ally. He has this mega prison holding a lot of the people who've been deported from the United States.

Reporters Without Borders have said that press freedom has massively deteriorated in El Salvador; with threats and state harassment, the seizing of equipment and the surveillance of journalists, more than 50 journalists have gone into exile. El Faro, a well-known independent outlet, has had to move to Costa Rica because all its journalists were under threat. MalaYerba has had to close.

I could mention other countries. Ali, with your experience working on Brazil, do you have any comments about the situation for journalists in Latin America or in other countries?

Ali Rocha: I've only ever worked in Brazil. Latin America is a massive area, so each country has its own specific themes and particularities.

In countries that have been under military dictatorships, such as Brazil, we see a lot of self-censorship. Some try to stay away from certain stories: it all depends on the situation in each particular country, with organised crime and politicians with criminal co-operation. Generally, I can't think of any countries where we can say that it is safe to carry out journalistic work.

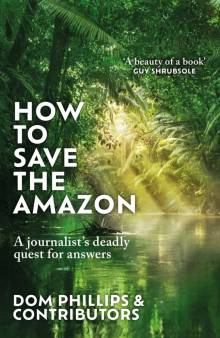

Ali then showed us the book that Dom Phillips was writing, How to save the Amazon, which was finished by a team of journalists and writers. She fold us “it was published on the anniversary [of Dom's disappearance] in June, and I recommend it. It was going to be How to Save the Amazon: Ask the People Who Know – that was the book that Dom wanted to write. But then it became How to Save the Amazon: A Journalist's Deadly Quest for Answers.”

No to impunity our symposium to mark the UNESCO day

No to impunity our symposium to mark the UNESCO day

![[Freelance]](../gif/fl3H.png)