Making our journalism necessary to people in Trump times

THE APRIL London Freelance Branch meeting heard from the current and former news directors of KBOO radio station, Portland, Oregon. They updated us on the state of free speech and journalism in the US under Trump v2.0.

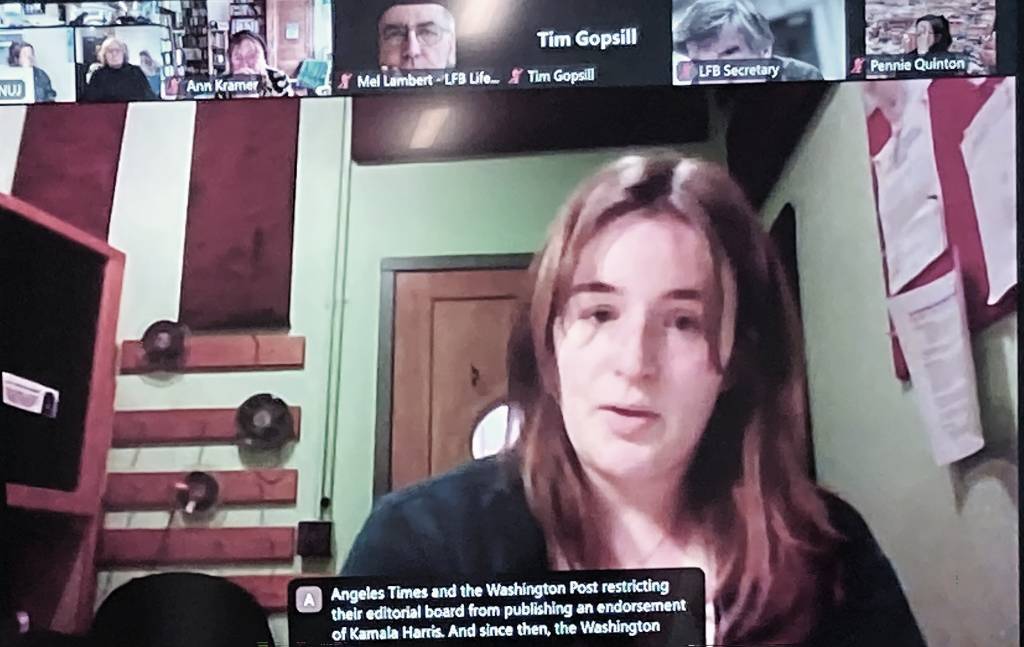

Althea Billings, news director at KBOO radio, on screen

KBOO radio started in 1964 when a group of Portlanders, disgruntled at the lack of a classical music station in their area, organised themselves into a collective called Portland Listener Supported Radio and launched a station with the call-sign KBOO. To this day the station addresses local broadcasting needs unfulfilled by commercial outlets.

Althea Billings, the current KBOO news director, and former KBOO news director, the intrepid journalist and coder Jenka Soderberg. spoke on survival in environments hostile to journalism by being there for their audiences and by keeping the focus local alongside the national and international.

KBOO serves minoritised groups, offering media access and training to provide a forum for controversial or neglected perspectives on important local, national and international issues, reflecting KBOO’s values of peace, justice, democracy, human rights, environmentalism, multiculturalism, freedom of expression and social change.

KBOO is unionised; workers are represented by a trade union called CWA Local 7901, part of the Communications Workers of America. KBOO is governed by a board of directors elected by its membership.

News director Althea Billings outlined Trump’s censorship of mainstream media in the US since February 2025. He has denied NBC News, the New York Times, National Public Radio (NPR) and Politico access to the Pentagon – so that these outlets no longer have an office to report from inside the US military headquarters building.

Trump has also banned the Associated Press agency from the White House press pool – after AP declined to change its style guide to refer to the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America”. This has a knock-on impact: smaller publications across the United States and the world rely on AP’s coverage of the White House and the presidency to inform their communities. “That's their lifeline” to those things, Althea said, and although a court had ordered AP’s reinstatement, this had not “totally come to fruition” as “parts of the Associated Press are still being left out of the Pentagon”.

Althea then described how the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which regulates radio broadcasting and television airwaves in the US, is investigating NPR and the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) TV stations. She explained the FCC is working on new complaints against ABC, NBC and CBS, the big three commercial broadcasters in the US. She mentioned that companies such as cable TV operator Comcast are being investigated for their Diversity, Equality and Inclusion (DEI) programmes.

Comcast oversees MSNBC, which has notably cut its hosts who are Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC).

Althea Billings: Just today, Trump was threatening CBS and the show 60 Minutes for covering Russia and Ukraine in a way that he didn't prefer.

Even some federal employees in the United States are having news sites like Wired, the Washington Post and the New York Times blocked from their computers. They're not able to access those sites. Yesterday or the day before our immigration system posted on Twitter about how they see their role as stopping ideas from crossing the US border. (They've now deleted that.)

Those are some of the more explicit acts of censorship that we're seeing on a national level. We've also seen plenty of larger organisations working to self-censor in different ways. Some of this happened even before the election with the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post restricting their editorial boards from publishing endorsements of Kamala Harris.

Since then, the Washington Post did a revamp of its op-ed page, limiting the types of opinions and the types of content that they would allow to be published.

Of course, you know, the Washington Post is owned by Jeff Bezos, one of those billionaires who are really kissing the ring, so to speak. He wants it to talk mostly about free markets and not about any kind of criticism of the billionaire class.

We also saw ABC settle a court case, and the likes of PBS, Disney, and other corporations in the media space cutting their DEI departments pre-emptively, to try to escape that kind of scrutiny – as DEI is the buzzword that the Trump administration is going after.

This is anecdotal, but I've noticed a change in the way that these publications are covering the Trump administration. I see, a sort of hedging language: the Trump administration “might have” this effect; it “could be considered” fascist. In recent memory those issues would be covered with a lot more explicit language, or the causal relationships would be evident. You could study this, if there were political scientists on the case...

Is there an impact from cuts to the funding of public media and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting on small independent stations like KBOO?

Althea Billings: it does impact us and it's tough, right? Because in the US, we've been talking a lot about how independent and non-profit media, even outside of the Trump restrictions, can be a salve to what we're experiencing, which is a loss of local publications, a loss of local journalism – things that are actually really important to communities, things that oftentimes independent non-profit media could be helping out with.

Funding does still matter, and non-profits are not out of the woods or out from under the scrutiny of the Trump administration.

There was an Act passed that gives broad authority to the federal government to declare non-profits to be “terrorist sympathisers”. I don't know if that law has gone into effect yet, but that was a seriously worrying one.

For smaller stations like us, we rely at least partly on grant funding from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB).

The way that that's structured is that the CPB is an independent corporation of the US government, which means that our funding for this year is secure, but going forward, it's definitely going to be more up in the air.

We don't rely on it nearly as much as some other stations do, but even folks not at the whims of the billionaires who own their publications are still in this limbo state.

Do the producers of KBOO programmes earn a living from their radio output, or do they do multiple freelance work?

Althea Billings: It's a volunteer-powered radio station. There's a staff of eight of us that keep it all juggling, keep it on air. The vast majority of our programmers are volunteers. They're committing volunteer time both in my newsroom and for all the other programming that we do on the radio station.

That includes eclectic music. We have shows in a bunch of different languages. We also have public affairs programming, more opinion-based talk programming. Most of those folks are doing that as volunteers.

Some of them have been able to spin that off into other career opportunities or build more of a podcast support, but for our radio station, they're doing volunteer work.

How does your membership model work to keep your station independent so you're not going to be bought by Jeff Bezos?

Althea Billings: I feel grateful for to be part of an organisation that has been doing this kind of work for so long. There's no real question that, once Trump was elected, we were going to change or to capitulate.

We get about 80 per cent of our funding from members. People listen to the radio station and contribute to us because of the programming they appreciate: $5 a month is the base level to be considered a member. Then they're able to be involved in the governance structure. It's also unique that we have that much support from the membership base, built up over the course of over 60 years...

We are very lucky especially in this moment, to be much more resilient than other folks because we have people in our community who continue to show up for us year after year.

Do you still have the original classical music programme that started the whole thing off?

Althea Billings: we don't play as much classical music – we do a lot of everything else. We've got jazz, we've got opera, we've got hip hop, we've got eclectic, weird sound editing things, nature noises, stuff like that. Anything you can think of, there's probably somebody at the radio station that's doing it.

And that is nice as well because it is a progressive voice and has that reputation, but we're on 24 hours a day with a lot of different things to offer folks and so there are people who really love the bluegrass show and that's what they fund and support, but it's able to keep the whole thing afloat, which is cool.

Also, something that we've seen, especially in getting donations from members in recent months, is that folks are supporting the news and want to support independent media and the ability for folks to be able to report on their own experience but also just the day-to-day living of what's going on in the US right now.

Our music blocks and our volunteer DJs are getting some extra attention just to be able to give people a break from some of that.

Jenka Soderberg on screen

Do you see things as being different for journalists from Trump's last term 2016 to 2020 - what do you see as the difference this time?

Jenka Soderberg: It’s definitely different this time around. In 2016, when Trump was elected, in our election night coverage at the station a lot of people were prepared to celebrate the first woman president. That still hasn't happened in the United States and, instead, we have this second term of Trump.

Now, during that time, KBOO wasn't funded by the CPB. It had previously been, but at one point lost that funding due to challenging the “free speech” rules back in the early 2000s. The National Public Radio Stations have CPB funding. The independence of our station was maintained and is maintained until now.

But I think now there's a different sense across the country, especially with the Associated Press being censored – which is unexpected, because Associated Press is so well known, so established.

The fact that just their refusal to use the “Gulf of America” resulted in them being kicked out of the White House? I don't think anybody was really expecting that.

And the Trump administration acted so quickly in its first month to crack down on journalists and bring in these hack people who don't have journalism experience, who maybe have a social media following on “Truth Social” or on one of the podcasts that Donald Trump is part of or that he supports.

So, it's basically bringing into the White House and the administration people who are yes-men for the administration.

I think it was happening a bit in 2016 to 2020, but a lot less than what's happening now, and has happened so quickly.

The good thing is that there's a lot of independent media in the United States that isn't subject either to the whims of the current government administration nor to the billionaires that own a lot of the media at this point. I think that's where the strength is.

There are over 240 community radio stations that are part of the Pacifica radio network. The five big ones are in New York City; Houston, Texas; Los Angeles and Oakland, California; and Washington, DC. Then there are hundreds of small stations run by the communities.

That's a big strength. Part of the print media, I think, has gone the way of the blogosphere – a lot of people post stuff and have news sites online. There's a lot of sites on Substack, for example, where independent journalists are getting subscribers and using that subscriber model.

And then, there are independent podcasts – and there's the big print media such as the New York Times, Washington Post and Los Angeles Times. I have come to depend less on them as sources of information.

What kind of audience figures did you have during the presidential election - what kind of listening figures were you getting on your political coverage?

Althea Billings: I don't have that specifically, but we have between 35,000 and 45,000 weekly listeners. It's a little bit funky, the way that it's measured in the Portland market, because it is a smaller metropolitan area.

Seeing the deportation order made against the student Mahmoud Khalil for his participation in demonstrations at Columbia University – how has this impacted journalists’ ability to speak truth to power, especially if they are naturalised American or have vulnerable immigration status working on some form of overseas visa?

Jenka Soderberg: I have heard of student journalists getting targeted at New York University and other universities. So that's a fear for student journalists, for sure, right now, because they're the beginning of the targeting that's happening. Like – first, they came for the students, right?

I think it is important to look at this in a global context when we talk, especially about Palestine. Where goes Gaza, there goes the world.

Right now, I think what we're seeing is the targeting of journalists, with US support. That's a dangerous precedent. US journalists aren't necessarily being killed for the work we're doing. In this past week in Gaza, some of you might have seen the video of them burning Ahmed Mansour from Palestine Today news agency outside the Nasser Hospital, when that airstrike hit a media tent.

The Israeli military claimed that it was targeting Hassan Aslih, who is a freelance photographer with hundreds of thousands of followers on social media. And Aslih was described by the Israeli military as a “terrorist journalist”.

He was wounded in the attack – which was an assassination attempt. If journalists worldwide are not standing up, it sets a precedent and it's dangerous.

For example, look at a different case altogether: that of Julian Assange here in the United States. He was targeted for doing journalism. People can argue “oh, he was doing something else” or “the government accused him of hacking”, but he didn't: he posted the WikiLeaks footage of US attacks on civilians in Iraq and that was then taken by many news outlets, including the New York Times and the Associated Press. So, any time a journalist is under attack, it's important journalists worldwide speak out and recognise that, especially when we're in a place of privilege where we aren't necessarily being killed for our work.

If this is allowed, it's going to be allowed in other places as well, especially when you have leaders who really believe “there are no holds barred” as with this administration.

How do you see the news echo chamber within the White House influencers and so-called journalists, and how that's going to change the dynamic of the media landscape in the US and particularly how it's affected journalists, and editorial standards across the board?

Jenka Soderberg: I think that a lot of people who are on the internet and use that as their source of news don't look to traditional media for the most part.

People get media shared from their friends, from their feed, from people that they trust. So, there's this trust factor that I think is the new kind of paradigm. What is legitimate media?

Everyone has a different sense at this point of what is legitimate media.

The one thing that traditional media has going for it is that it has traditionally been based in fact-checking and trying to ascertain the source of the information that they're sharing – not just jumping into conspiracy theories.

Now, anyone can say anything and as long as it spreads, it can be repeated by many people as potentially true.

It's important to have fact-checking sites such as Snopes or others, looking into things that are getting spread widely, like viral claims, and actually debunking or looking into the actual sources to find out if they're based on something that’s real.

That's where our legacy media comes in: it’s looking for the source of the information. Having people who have those skills and who have that kind of critical thinking is essential.

I don't think we need to depend on the legacy media to do that. I think anybody can develop those skills, but that's going to be important as things get thrown around and influencers well, influencers are influencing. That's what they do. We must look for the source that's the key.

The US tends to lead most of the world affairs – if this is happening in the US, how does it spread across the world? If the current administration is openly intimidating media houses, suing them, pushing them out of the press pool how does this affect journalists like yourself?

Althea Billings: It is a very scary time – and, as you say, the US does have this history of leading the world. In 2016, we lost a ton of legitimacy in terms of leading the world, and I think that that is probably going to continue.

In the room

How do you battle this current government and media houses like Fox News, that are on the side of the government? How do you navigate between the government and your own colleagues who should be standing beside you trying to fight these intimidations?

Althea Billings: When I think about how we combat the likes of Fox News and this much more polarised media: there's so much that's out of my individual control.

I could tell everything that I think that my audience needs to know, but it doesn't necessarily change the fact that some of them may still have Fox News on in the background, or maybe that's what their family listens to or has on.

There has been a longstanding erosion of trust in journalists from individual people. And so, what we must do is engage with them, answer their actual concerns.

And sometimes that isn't the flashiest kind of reporting, we're in tough economic times and scary times for a lot of different reasons: and so I am thinking about how we make our journalism necessary to people, and how we make sure that what we are trying to communicate with them is something that they can really engage in?

And how can we carry forward into their day, because becoming a part of somebody's life and becoming that trusted source – it's nice to be a part of an institution that maybe has earned that over time.

I certainly have benefited from that. But part of it is also showing up and continuing to do the work that you have been doing. Because that's the integrity that people look for and know they can turn to you when they need help.

What gives you hope, even in a post-truth world, and as journalists and broadcasters what are your hopes for the future?

Althea Billings: People ask me that all the time, especially how you digest information and continue – because I am in a putting-out-a-daily-newscast kind of grind, I have had to focus on local politics.

Thinking about our local area, our local politicians – we in Portland are very lucky in having a progressive surge. We just created a new form of government that's just taking over. There’s representation that we've never had before. So, as much as the country is backsliding, where we're living there is potential for new forays into being able to support people. So, I encourage a focus on the local where possible, right?

And we have to focus on the national beat, of course, but it is overwhelming to see all these things that are happening and that might be against your values but feel unable to make a change.

Focusing on those individuals and those at local level is something that can keep a more positive spin – to be able to see that there is change being made and that people care and are resisting. Even if we throw our hands up and say “there's nothing that can be done” – I don't agree with that but being able to see that there is action and that there is a diversity of opinions, of people looking at the media landscape and looking at the governmental regime, I think is important.

I was wondering what support network you've got from colleagues either in the labour movement or in the community.

Althea Billings: Labour is a big component of KBOO, fortunately.

We are a union shop. I'm one of the stewards. We're with CWA 7901 so not in the News Guild, which is typical of media organisations here.

Some of the independent publications that we have around us are taking up with CWA or starting their own. We also have a weekly public affairs show on our radio station called Labor Radio. That's hosted by a rotating cast of unionists from different shops and different organisations.

It's been a real pleasure to hear from you both stay safe. If you ever need anything from the NUJ, then please come to us because we'll be here in solidarity. Thank you.

Please take a minute’s silence in your own time to remember fallen colleagues

Jenka Soderberg had wanted to lead a minute’s silence to remember the journalists burned to death in the Israeli air strike on 6 April but due to connection issues she was unable to do this. Jenka sent the following text that she had intended to share with us to introduce the minute’s silence. Please observe your own silence in private as you take a moment to read Jenka’s text.

First we just would like to take a moment to recognise fallen journalists. On 6 April an Israeli airstrike targeted the media tent outside Nasser Hospital, where journalists were working to prepare and upload footage to news agencies.

Ahmed Mansour, an editor with the Palestine Today news agency, and his co-worker Hilmi Al-Faqawi were among those killed in the attack.

Ahmed was seen on video sitting at his desk, burning alive and unable to move due to a beam that had fallen across his legs.

Yousef Al-Khozindar, a 27-year-old fixer working with NBC News’ crew in Gaza, was also killed in the strike.

The Israeli military claimed that it had been targeting Hassan Aslih, a Gaza-based freelance photographer with hundreds of thousands of followers on social media. The military described him as a “terrorist journalist”. Aslih was wounded in the attack. The Israeli military claimed that he had uploaded footage of violent acts, and was therefore a legitimate target for assassination. For the record, journalists documenting the violence of war are protected under the Fourth Geneva Convention, specifically Article 79 of the Geneva Conventions' Additional Protocol I, which states that they should be considered civilians and afforded the same protections as other non-combatants in armed conflict.

Let’s take a moment of silence to remember these colleagues who were killed while doing their work of documenting the reality on the ground in Gaza.

Thank you. According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 2024 was the “deadliest year for journalists” around the world, with Israel being “responsible for nearly 70 percent” of those killed. Last Sunday’s airstrike brought the number of journalists killed in Gaza since the start of the war to at least 219.

Remember the dead – and fight for the living! vigil 28/04/25

Remember the dead – and fight for the living! vigil 28/04/25

![[Freelance]](../gif/fl3H.png)